Lissala

- “No -worthwhile reward comes without -work, service, or sacrifice,

- —Devotion to the Seven Forms

Présentation[1]

Lissala (lis-sall-uh) est une déesse des arcanes autrefois adoré par les azlantes et les thassilonians. Elle est précise, rigide, diligent, et intolérantes envers la désobéissance, et sa magie et philosophie étaient essentiels à la réussite de l'ascension de thassilon comme empire. De même, le lent rejet de sa foi dans l'empire thassilonians durant ces derniers siècles a grandement contribué à sa chute. Il semble qu'elle s'est retirée de Golarion et n'a plus aucune présence connue dans l'au-delà. La plupart des sages modernes supposent qu'elle est morte, englobée par une autre divinité, ou a voyagé au-delà des plans connus à la recherche d'une sagesse infinie. Les gens du commun en Varisie qui découvrent ses runes les attribuent aux rune des géants ou des cultes démoniaques. Cependant, il semble que certaines des runes magiques de thassilon conservent un lien avec elle et des rumeurs sur de nouveaux prêtres consacrés à cette déesse absent et presque oubliée se répandent.

L'origine de Lissala est inconnue, comme il n'y a pas d'enregistrement Azlant qui expliquent comment elle est devenue une déesse ou quand elle est intervenue pour la première fois dans le monde des mortels. Elle aurait pu être une création des constructeurs de coffre, une descendante du peuple serpent ou une mage Azlanti ayant atteind l'état divin, une première tentative par les aboleths d'établir un contrôle sur les terres arides, ou l'un des premiers mortels a apprendre et perfectionner la magie des dragons. Peu importe comment elle est venue à être, elle fut une divinité bien établi pendant l'empire Azlant, et (contrairement à plusieurs autres dieux Azlant) son pouvoir a survécu après la chute en grâce des Azlants à permis au fondateur Xin de Thassilon de faire de sa religion un élément clé du nouveau pays .

Au summum de son culte, elle était généralement à l'écart, mais répondait aux questions de ceux qui avaient le désir d'apprendre et la volonté de travailler pour la connaissance. La plupart des chercheurs croient que son éventuel retrait de Thassilon était probablement délibérée, mais si lent que la plupart de ses fidèles n'ont jamais réalisé ce qui se passait.

Comme déesse du dure devoir et de l'obéissance, elle représente la puissance acquise par la pratique, l'étude et la déférence pour un maître. En tant que tel, elle est favorisée par des sorciers plus que par les autres lanceurs de sorts profanes (les bardes et sorciers particulièrement, qui développent la magie par eux même ou sont encouragés à défier l'autorité). Elle est intolérante envers l'insolence et la désobéissance, et soutient l'utilisation des châtiments corporels ou des formes magiques de discipline (y compris les malédictions temporaires et transformations) pour les futurs assistants qui n'apprécient pas leurs mentors. Les apprentis la prient afin qu'ils puissent s'acquitter de leurs tâches essentiellement sans que leurs maîtres ne les punissent de façon déraisonnable pour leurs erreurs; les magiciens prient pour que leurs apprentis soient efficaces, talentueux, et soient valables pour le temps que son maître a perdue, pour son stupide ou incompétent apprenti c'est au mieux inutile et au pire dangereux.

Comme divinité de la récompense des services, elle enseigne que les seules récompenses valables sont celles qui viennent suite à de nombreux efforts. Tout donnée comme cadeau est d'une valeur douteuse, et le récepteur doit se méfier de la motivation de la source. Il est demandé aux apprentis que leurs esprits soient ouverts à tout ce que leurs maîtres peuvent leur enseigner; les assistants demandent que leurs élèves soient reconnaissants pour les connaissances qu'ils leurs sont donnés, et qu'ils deviennent des alliés utiles une fois qu'ils seront autonome.

Comme déesse du destin, elle a une relation compliquée avec Pharasma (qui a également été adoré à Thassilon). L'aspect des sorts de Pharasma est étroitement liée à la prophétie de discernement et de l'épanouissante, alors que l'aspect des sorts de Lissala est plus sur l'acceptation des charges nécessaires, de la persévérant malgré les difficultés, et de la planification à long terme. Elle considère la magie de divination indigne d'étude. Non seulement elle ne la considère pas comme une véritable école de magie (elle n'est pas, en fait, associé à l'un des sept types de magie runique), mais elle croit que cette aide contourne les méthodes appropriées d'apprentissage. La divination n'est pas interdite, mais dédaigné par les fidèles comme la marque d'un amateur. Les Adorateurs sont encouragés à planifier leur vie et les années de recherche magiques à l'avance. Par exemple, ceux qui planifient de devenir liches généralement alloué chaque année du temps pour faire avancer cet objectif, même durant l'apprentissage.

As the goddess of runes, her touch is in every spellbook, every graven glyph, and every sigil and symbol spell, as well as on the flesh of every rune giant, whose race owes its existence to Lissalan rune magic. She teaches that writing is power, whether magical writing or letter-runes used to preserve or convey knowledge. Her followers would sooner burn their own flesh than burn a book, and in her church it is considered a high honor for the dead to have their skin tanned into vellum for use in spellbooks and religious texts, forever associating the person’s remains with magic. The living worshipers prize these books, and a mentor may award such a tome to a journeyman priest or wizard who worked hard or who showed great talent. Tattoos and branding are common among the faithful, and some worshipers even have the text oftheir favorite books or spells etched upon their flesh while still alive, in anticipation of becoming books once they are dead.

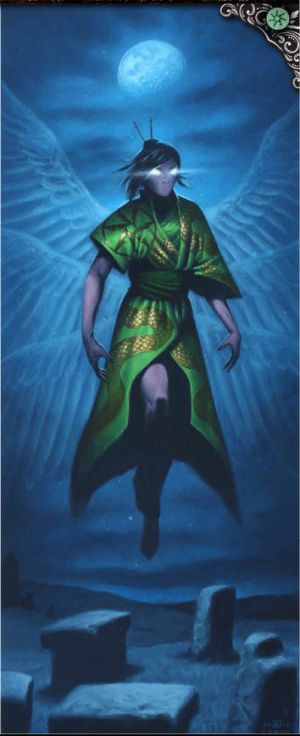

Lissala manifests as a stern-looking, fair-skinned woman, likely ofAzlanti descent, but there is something strange and alien about her eyes, and she has no mouth—the lower part of her face is smooth flesh, though she is able to speak and cast spells as if she had a mouth. She normally appears wearing severe robes of green and gold, usually with a snakeskin pattern and a Sihedron rune, and faintly visible on her back are six ghostly, transparent bird wings. Alternatively (especially when she expects battle), she sometimes takes the form ofa lillend-like creature with a snake body, wings, and a Sihedron in place of her head. In her presence, time feels slightly stretched, and spoken words and spells often briefly manifest as illusory writing around the speaker. In art she is usually depicted in her humanoid form, though her “battle form” is favored in murals commissioned by evokers and wrath-priests. She is often accompanied by snakes—either actual snakes, snakes of pure energy, or elements of her clothing animating in the shape of serpents.

Lissala shows she is pleased through the momentary appearance ofher strange eyes, snakeskin patterns or subtle runes materializing on paper or stone surfaces, and single peals of deep-toned bells. She may cause a spellcaster to retain a prepared spell after casting it or prevent a scroll from fading when used. When she is angry, work slows, writing becomes incomprehensible, plans are delayed, and minions disobey their masters or mishear commands.

Lissala is lawful evil and her portfolio is runes, fate, duty, obedience, and the reward of service. Her favored weapon is the whip. Her holy symbol is a variant of the Sihedron rune, though practitioners of rune magic sometimes use a symbol of a whip twisted into the shape of their keyed rune. Her domains are Evil, Knowledge, Law, Nobility, and Rune. During Thassilon’s heyday, she was revered by most of the population as the goddess of magic, but now her faith is all but forgotten by humans and only persists among rune giants, as her faith led the Thassilonians to create their race. Rumors of scattered cults of Lissala appear in some parts of Varisia, but there is no organized, public institution ofher religion. Historically, most ofher priests were clerics, with some especially devout wizards taking roles in the church hierarchy. Among the scattered modern cults devoted to her, the proportion is closer to half and half with a few oracles (usually with the bones, flame, or lore mysteries) making an appearance. All have ranks in Knowledge (arcana) or Knowledge (history); otherwise, others in the cult would not respect them.

Snakes, nagas, and magical ophidians (including couatls and lillends) are sacred to Lissala’s church. The faithful avoid conflicts with such creatures, even if there are alignment issues (such as an evil priest with a lawful good guardian naga). Her followers dislike magic-destroying creatures and things that consume books and other writings, including mundane creatures such as silverfish and moths. This opposition to moths (and butterflies, due to overzealous precautions) often starts feuds with Urgathoa’s and Desna’s followers. Some Lissalans take this aversion to moths to such an extreme that they refuse to wear garments made of silk, though this is not required by the goddess.

A typical worshiper ofLissala is a wizard, cleric, scholar, historian, or taskmaster. The faithful perform magical research, train others to use spells, use their knowledge to fortify their communities, or magically control creatures for that purpose. They are hard-working, driven, fastidious, and used to slow progress toward goals.

Worship services involve reading aloud and transcribing scrolls, spellbooks, or Lissala’s holy text. Priests create or reinforce the magical wards in and around the temple and report progress on magical research. Apprentices and acolytes have almost no role in temple ceremonies, as they have not yet proven themselves. During services these minor members of the church busy themselves fashioning quills for writing; grinding styluses for scribing stone or clay; preparing parchment, vellum, and paper; polishing stone plates for scribing; or firing marked clay tablets.

Lissala teaches that marriage is an excellent cultural tradition and a long-term commitment between two (or more) people. Whether a marriage is for love or arranged for political or familial purposes, she expects spouses to fulfill their marital oaths, and is intolerant ofadultery or other violations of the expected contract. She expects that one person in the marriage is dominant and the other(s) should defer to that one. She does not require this pattern of dominance to be defined in the marriage oaths, though if the spouses wish to do so, it suits her. Members of the church are not required to have children (whether they are conceived naturally, adopted, or magically created), but children are expected to obey their parents or guardians. Parents may raise their own children or rely on employees or an external institution to do so for them.

Temples et Sanctuaires[1]

Temples are traditionally built or carved from dense stone, and constructed to last for hundreds of years. Wood is too combustible and brick is too fragile (especially against earthquakes) for a sacred space devoted to the goddess. Many holy sites are made of magically conjured stone or by creating chambers in natural rock with acid, disintegrate spells, or the work of enslaved giants. The entry and ritual chambers are usually septagonal and decorated with a large Sihedron mosaic. During the era ofThassilon, most of the temples adopted one of the seven vices as a theme (usually associated with the runelord who controlled that territory), but this was not a requirement, and there are a few temples that are not dedicated in this fashion.

The few people living today who have explored Lissalan temples may assume they are hidden, convoluted affairs with traps, but those were only nominally temples and primarily served as secret places to perform obscure rituals in service to the runelords. During the time of Thassilon, Lissala’s worship was public and common, and her temples had a very different structure. A typical public temple was a large, sprawling building or complex with spaces for many priests, servants, and slaves to live and work, with kitchens and food stores to support all of the temple’s inhabitants. Most activity related to the crafting and maintenance of spells and items to protect and expand the reach of Emperor Xin or the runelords; this required creating parchment and vellum, inscribing scrolls or glyphs, carving blocks into runestones, inscribing weapons and armor with protective runes, practicing means of magical tattooing and branding, and so on. Amid all of this activity, priests whose labors had earned them time to study established lore or to engage in magical research, usually in secluded rooms that muffled the noise of the temple’s other activities. Most temples also contained a small cemetery or crypt for important members of the faith who had passed on. These features made the Lissalan temples much like self contained cities or fortresses and allowed the priests to survive the many food riots that happened as Thassilon declined.

Shrines to Lissala were common, typically human-sized blocks of hard stone graven with the Sihedron rune and traced with dozens of smaller runes, often added long after the original stone was consecrated. Green marble and gray stone with flecks of gold were the most common types of stone used for the shrines. Often these shrines were used to store, direct, or reinforce wards or other magical effects, such as magic that prevented slaves from rebelling. Many of these shrines have a lingering magical power, long dormant but still waiting for a priest to awaken them.

Rôle du Prêtre[1]

Priests are taught that obedience to one’s superiors is absolutelynecessary, that following orders is a minorform of prayer, and that the goddess awards knowledge to those who serve faithfully. Every priest knows exactly whom she reports to in the church hierarchy and exactly which underlings she can command, as well as whose instructions are merely suggestions and whose minions are to be left alone. Each day is a regimented list ofactivities, with work, worship, meals, leisure, celebration, and sleep all given specific time periods so the temple as a whole functions smoothly. To deviate from these plans causes disruptions; for example, being late to a meal means the kitchen is overtaxed feeding extra people at a certain hour, loud worship or celebration at inappropriate times may awaken others scheduled to sleep at that time, and so on. Priests quickly learn the value of this kind of scheduling and tend to anger quickly when dealing with others who are more relaxed about schedules and deadlines.

In an adventuring party or even a common travel situation, a priest likes to create a schedule for the group and expects everyone to comply with it, including brief rests during the day and assigning who is on watch at night. If the priest’s companions fail to comply, the priest may retaliate by exaggerating her activities to bother others, such as praying loudly to herself when others are trying to sleep.

Priests appreciate others who are knowledgeable and willing to teach about an area of expertise. For example, if a priest has no interest in or talent for battle tactics but travels with an experienced mercenary or military officer, the priest looks to that person for advice in combat about which foe is the most dangerous, which allies are expendable, and when to retreat. A smart priest is able to compartmentalize when he is directing others (such as by setting a schedule for a caravan) from when he should follow another’s orders (such as obeying an officer’s battle commands). Others may find the transition from bossy schedule-maker to taciturn battle healer jarring and uncharacteristic, but to the priest it is a well-developed coping mechanism learned in a temple of complex overlapping hierarchies.

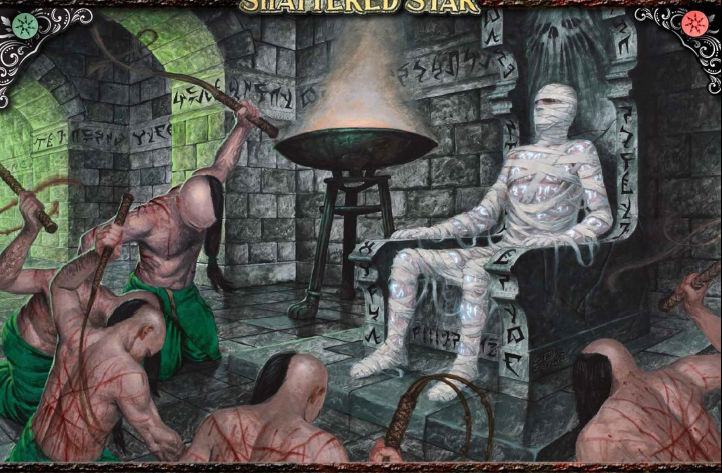

As Thassilon grew more decadent, so did Lissala’s priesthood, though this was a reflection of the country’s culture and not a directive of the goddess. In earlier centuries, the church encouraged lazy acolytes to seek careers outside the priesthood and sold weak-willed slaves to other temples; over time the priesthood hardened and flagellation became a common practice among underlings and slaves, either as punishments for minor errors or for the gratification of the superior clergy. Lissala’s whip became an active threat rather than a subtle reminder of encouragement. Each temple adopted one of the seven vices and focused its magic on that vice. Self-mortification became common practice; priests branded runes into their flesh to show their devotion, impress colleagues, and purge weak impulses and rival vices from their bodies. Senior priests often had dozens or hundreds of runes decorating their bodies, and learned how to invest these runes with power, much as was done with the creation of rune giants. The factions within the churches delved deep into magical research and unlocked great and terrible powers: gluttony priests created rituals to turn themselves into vampires, sloth priests slowed their metabolisms and lived in a dream-like meditative state for weeks at a time, and so on. Over time, these practices became more important to the priests than actual worship of Lissala, and their divine powers weakened even as their arcane mastery improved. These acts did not conflict with Lissala’s teachings (and were practiced for decades by priests in good standing), but when secular ceremony becomes a replacement for true devotion and worship in any religion, a cleric risks losing the connection to her deity that powers divine magic. Eventually, Lissala was only granting spells to a few members of the priesthood, with the rest having long since become arcane spellcasters or magical beings (including Runelord Krune, her high priest).

With the fall of Thassilon, her few remaining priests went into hiding or suspended animation (or became undead). They instructed their followers to practice the goddess’s teachings in secret and persevere until the time came to awaken the leaders. Most of these hidden cults also revere the seven sins rather than being purely devoted to Lissala, but this may change if she returns in full force and unites her scattered followers.

A priest usually has a mental list or schedule ofthings to accomplish each day. These efforts are coordinated with others in the cult, working together toward a distant but achievable goal. In civilized lands, her priests may pretend to be followers of Nethys or Pharasma, speaking words of wisdom about magic and fate. In evil lands they may pretend to serve Asmodeus, encouraging obedience and diabolical conjuration. Her priests are patient and methodical, enduring hardships, indignity, and the inner outrage of speaking false prayers to another god instead of true ones to Lissala. Ifa priest follows a mortification cult, a hidden space on her body may be the site of many overlapping cuts—a secret ritual of faith and obedience to honor the priest’s true beliefs.

Formal dress for the clergy is a tan or yellow robe with a billowing green cloak. Snakeskin and Sihedron decorations are common but are not required except for higher-ranking clergy. Ceremonial garb may include a snake-patterned skullcap and a metal frame worn on the shoulders that supports several majestic but fragile wings crafted of wire and bird feathers. Scars, brands, and tattoos in the shape of runes are common (especially in mortification cults) but not necessary.

Traditionally, the church ofLissala was heavily involved in the local community, contributing magic to build defenses and providing slaves and charmed minions to assist in tasks throughout the city. For a secret cultist, interaction with the community follows a similar role to whatever faith the priest is emulating, though usually emphasizing service.

Texte Saint[1]

The official holy book of the church is Devotion to the Seven Forms, consisting ofeight chapters. The first chapter explains the tenets of the faith, with the others each explaining one of the seven worthy schools of magic (abjuration, conjuration, enchantment, evocation, illusion, necromancy, and transmutation), and emphasizing the relationship between runes and magical power. In the most valuable copies, the opening page of a chapter is made of human skin donated by one of the faithful, and the introductory text was tattooed or branded on it while the person was still alive. Most copies of her book were lost or destroyed in the fall of Thassilon, and those in the hands of sin cultists may have been revised to inflate the importance of their chosen sin.

Aphorisme[1]

Because her faith changed much over the last few hundred years ofThassilon and the surviving cults are hidden and may be practicing corruptions of her original teachings, it is unclear which phrases date back to the original faith, as none are direct quotations from her holy text.

Jours Saints[1]

The holy text describes various holidays associated with stellar conjunctions and their specific relationships to the seven schools of true magic. The decadent church has added its own holiday and ritual tied to rune magic.

Feast of Sigils: In its original form, the priests held this ritual on 3 holy days during the year. The feast links the souls of the participants—drawing their power into runes drawn in wine, wax, blood, perfume, and food— amplifies this energy, then returns it to the feasters, who gain more than what they put in. In decadent Thassilon (and in modern practice), nonspellcasters joined the feast, inadvertently losing their life energy to the feast, which increased the power ofthe priests.

Relation avec les autres Religions[1]

Lissala is an evil goddess but had amiable relationships with all the deities of Thassilon, even Desna (though modern Desnans would have little love for her church). She had a fierce rivalry with Amaznen, the Azlanti god of magic, but he may have been killed during Earthfall and his worship was outlawed in Thassilon, leaving her supreme in magic. In modern Golarion, she has had no interaction with any known deities for thousands of years.

Nouveaux Sorts[1]

Clerics ofLissala may prepare sepia snake sigil as a 3rd-level spell and explosive runes as a 3rd-level spell. In addition, her priests have access to the following spell.

Lissalan Snake Sigil

School see text; Level cleric 3, sorcerer/wizard 3 (Lissala) Duration permanent until discharged; 1 day/level; see text There are seven variants of this spell, one for each ofthe Thassilonian schools of magic. Each functions like sepia snake sigil (and counts as that spell for the purpose of combining other spells that hide or garble text), except instead of trapping the subject, the triggered sigil’s effect depends on this spell’s school. This effect lasts for 1 day/level. This is a curse effect that can be removed via remove curse.

Abjuration: All beneficial magical effects on the target last half as long as normal.

Conjuration: The target is nauseated. This is a poison effect.

Enchantment: The target takes a id6 penalty to Intelligence, Wisdom, and Charisma. This is a compulsion effect.

Evocation: The target gains vulnerability to an energy type, chosen randomly from the following: acid, cold, electricity, or fire. This is an acid, cold, electricity, or fire effect.

Illusion: The target’s vision is blurred, giving it a -4 penalty on Perception checks relating to vision, and the target treats all other creatures as having displacement. This is a glamer effect.

Necromancy: The target is exhausted. This condition cannot be removed with rest.

Transmutation: Target is affected by slow.

Customized Summon List

Lissala’s priests can use summon monsterspells to summon the following creatures in addition to the normal creatures listed in the spells.

Summon Monster VI Advanced kyton evangelist (lawful, evil), Dark naga* (lawful, evil)

- This creature has the extraplanar subtype but otherwise has the normal statistics for a creature of its kind.